957 views

Kokkarebellur: A Village Built Around Nests

By Rahuldev Rajguru

Last Updated: 04 Apr 2023

As I readied for the next bird photography excursion, my excitement was palpable. I meticulously cleaned my camera and lenses, and packed my tripod. The destination was a tiny remote village in Karnataka where thousands of migratory Painted Storks and Spot-billed Pelicans were nesting in their natural habitat.

These birds are large but notoriously skittish around humans. Even being 300 meters away won't cut it - they will spot you moving around in search of the best location and flee before you could find one. That's why I brought my tripod to keep my camera steady while shooting from a distance. Little did I know that I would never have to use it as these feathered friends were surprisingly and wonderfully unfazed by my presence just a few feet away. For a wildlife photographer like me, this was an unprecedented experience, and my heart was full as I captured stunning close-up shots of these magnificent creatures along with their adorable offspring by their sides.

A mother with two babies in her nest

Kokkarebellur is a tiny hamlet in Maddur Taluk of Mandya district in Karnataka, about 90 km from Bangalore. The place had been buried in the depths of my memory for years, until a serendipitous social media post led Chirag (a friend of mine) and me down its dusty roads at the crack of dawn. This was our long-awaited wildlife trip after BR Hills Wildlife Sanctuary and Kabini Tiger Reserve, and I couldn't wait to see what this quaint little village had in store for us. Nothing compares to witnessing the feathered creatures in their natural habitat as they greet the morning sun with vibrant energy. Therefore, I always get there before sunrise. As an avid birder and photographer, I know the importance of catching them during the golden hours for the perfect shot.

Entrance to Kokkarebellur village

The wooden-looking open gate with painted stork carvings welcomed us as we reached Kokkarebellur. A few painted storks were already in the sky, so excitement was building. We didn't know where to look for birds. We only knew there were hundreds of them on tamarind trees. As we drove along, the sound of bill clattering and wings flapping suddenly filled the air, bringing us to a screeching halt. I knew the painted storks were nearby, but all I could see was buildings - that is, until I turned my head to the left. My heart skipped a beat as 100 meters from our car was a tamarind tree with a palette of colors. While my friend was still searching for them, I shrieked..."Over there!"

Kokkarebellur is home to migratory painted storks that spend months nesting in the tamarind trees

Kokkarebellur Village, a paradise for bird enthusiasts

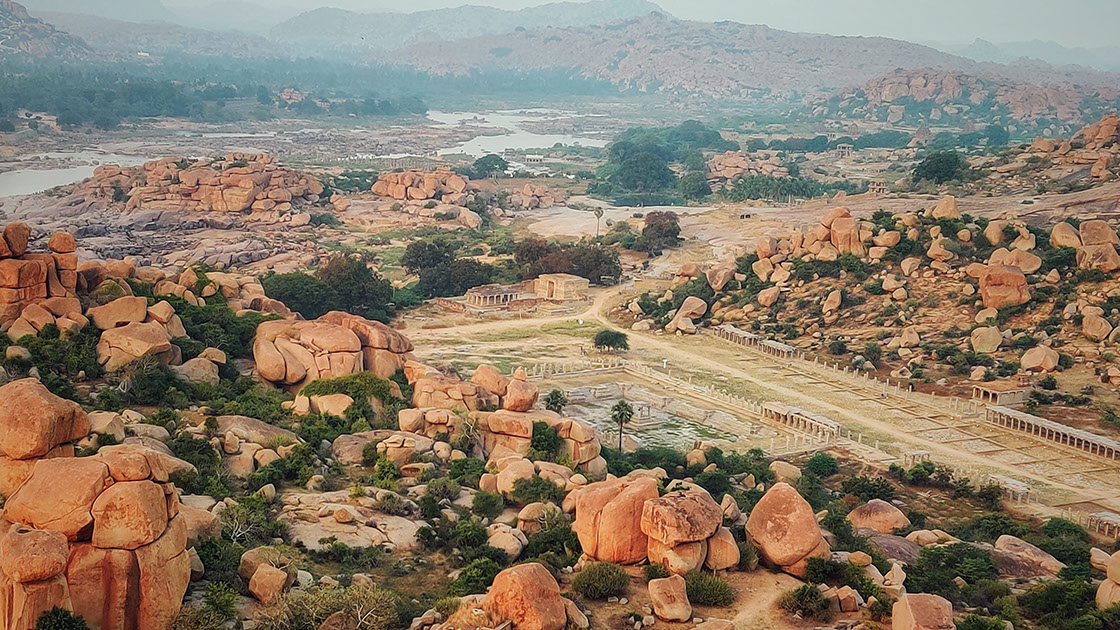

Kokkarebellur is a typical South Indian dryland village. Nestled at an altitude of 2,500 feet, this village is a true haven for bird enthusiasts and nature lovers alike. With the picturesque Shimsha River nearby and a population of 2,000 warm and friendly locals, you're sure to feel right at home in this serene setting. The majority of residents make their living through farming and animal husbandry. The rich red loamy soil of this area produces a variety of crops, including sugarcane, paddy, coconut, and ragi.

The bullock cart is still the main mode of goods transportation in Kokkarebellur

Kokkarebellur was first introduced to the world by the British Naturalist, T. C. Jerdon, in 1864. As he described the village, he referred to it as Pelicanry, where pelicans built their nests in low trees in the midst of human activity, seemingly unconcerned with the people's constant presence nearby.

Kokkare in Kannada means painted stork, while Bellur means white village, which denotes sugarcane. This village has a unique bond with spot-billed pelicans and painted storks, which it has adopted as part of its local heritage. As a result, Kokkarebellur gets its name from these birds, which have been migrating here for over 300 years.

The beautiful Kokkarebellur is home to migratory painted storks for six months of the year

Symbiotic Sustenance

Step into the picturesque village of Kokkarebellur during the months of August to December and you'll find yourself transported into a charming forgotten era of Karnataka. Stroll down the narrow avenues dotted with quaint old-world houses, lifted high above the ground, decorated with intricate teakwood pillars, and tiled roofs.

In the village, things are pretty quiet as the days tick by. But don't be fooled by the peaceful facade - come January, something truly incredible happens. The village undergoes a stunning transformation, as flocks of spot-billed pelicans touch down and are soon followed by painted storks after a few weeks. Thousands of migratory birds descend upon the village, claiming the vacant upper floor of the village as their own. Each and every tamarind and banyan tree is filled with these special guests, with chirping and fluttering in every branch. Their constant clatter fills the air, making the formerly silent village burst with life. It's like when school's out for summer and suddenly all the kids descend upon their grandparents' house - a once-quiet place is now teeming with activity. For the next six months, the birds work overtime to build their nests, hatch their eggs, and keep their young fed. It's a wild and wonderful sight to behold!

Kokkarebellur is an ideal example of harmonious coexistence between humans and birds.

A spot-billed pelican rests on a perch unfazed by my presence as I take its picture

There is no clear reason why storks and pelicans, both predominantly fish-eaters, continue to breed in Kokkarebellur, a village several kilometers from substantial water bodies. Generations of both species have come here to breed. They seem to have a special bond with this place.

Kokkarebellur's livelihood patterns reflect its symbiotic relationship with nature. The agriculture in this village has flourished as a result of the use of manure prepared from nutrient-rich bird droppings (guano). Residents dig pits around trees to collect bird droppings, which are later mixed with cow dung and silt to make manure. The birds in Kokkarebellur generate 120 kg of Guano each year. Three full tractors of manure can be produced from just 10 kg of Guano mixed with other substances. Using Guano in manure helps increase agricultural yields by five times. What a perfect ecological balance!

Kokkarebellur: where humans and birds coexist in harmony

A bond that goes back centuries is rooted in cultural elements that are deeply ingrained in the local community. Probably this is the reason why these birds, which are usually shy of humans, prefer proximity to people. At the Nature Interpretation Center, I was informed that the residents treat all birds (not just storks and pelicans) as their own daughters who traditionally deliver babies in their natal homes. The birds come here year after year because they feel safe and at home. A bird nesting in one's backyard is considered a sign of prosperity, and residents prefer to marry their daughters into such households. In order not to disturb the birds, they don't even harvest Tamarind pods during nesting season. For generations, residents have taught their children not to tease birds or destroy their eggs.

Black-crowned Night Herons are also residents of this village along with storks and pelicans

Kokkarebellur celebrates the "Feast of the Village Deity" festival every year. It was part of the celebration to burst a lot of firecrackers. The residents decided to abolish the practice of bursting firecrackers 20 years ago out of respect for their migratory guests. 30-40 storks and pelicans used to die from electrocution every year. A few years ago, Chamundeshwari Electricity Supply Company spent a whopping INR 45 lakhs (4.5 million) to insulate all electrical cables throughout the village in order to prevent accidental electrocution of birds. Residents of Kokkarebellur have set an example for joining hands in preserving this biodiversity hotspot.

An unforgettable morning stroll in Kokkarebellur

Residents encouraged us to take a stroll in the village to get a more realistic picture. The village's roads are laid out with RCC (cement) and are kept clean and tidy. In order to reach Kokkarebellur before sunrise, we did not stop on the way and soon hunger set in. We reached the main road near the KSRTC bus stop, where there were a couple of eateries. We were welcomed by a family who served us hot idlis, sambhar, chutney, and bhajji. The food was delectable.

Delicious breakfast in Kokkarebellur

The vibrancy of the village dwellers was palpable and they welcomed us with open arms, eager to learn about our stories as much as we were to hear theirs. Despite our language divide, I managed to keep the conversation going with my 'sulpa sulpa' Kannada, and the connection we shared was a joyous and heartwarming experience.

As I set out to capture some stunning bird shots with my camera, I quickly realized that I needed an elevated viewpoint. After hesitating for a moment, I mustered up the courage to approach a resident and asked if I could climb up to their terrace. To my delight, they welcomed me with a gentle smile and even asked what I planned to do with the photos. As a bird enthusiast, I sensed their caution not to disturb the precious nesting grounds. I was well aware of the fact that during the nesting period, birds are highly sensitive to intrusions. They might abandon their nests and eggs if they feel threatened. However, when I shared my plans to write about the village and the ecosystem, their eyes lit up with enthusiasm and receptiveness. The experience left me feeling grateful for the kind and friendly locals.

One of my best shots of a stork couple in their nest from the terrace of a house

As we wandered deeper into the village, the greenery grew denser and the air filled with an uproar of clatter. Every tree in sight appeared to be the nesting ground for about 30 stork families - an incredible display of nature's unbridled beauty. I've seen storks before, but never this close and carefree around people. They even flew within 10 feet of me, as if giving a friendly wave. The sound of their wingspan was awe-inspiring, and it was amazing to see these birds dominate the skies. For the first time in my birding experiences, I saw more storks in the sky than crows and pigeons. Watching them break branches off trees to build their nests was a personal highlight of my time in Kokkarebellur.

The sight of a painted stork carrying a perch in its beak is spectacular

Eventually, we came to the end of the village, where we found a small park with old banyan trees. There were benches and a gazebo where one can relax and listen to storks clattering continuously. In addition to storks, you can also observe many other types of birds in these trees. According to some locals, this park used to be the earlier Nature Interpretation Center that later moved.

Park is almost entirely shaded by dense banyan trees

As we hung around here, I noticed several birds. I discovered later that Kokkarebellur is home to 135 species of birds. It seems that this is a popular spot for locals to spend their leisure time. I had a good conversation with the locals. These are some of the birds I could click here.

Tickell's Blue Flycatcher

Indian Robin (Female)

Brahminy Kite

Spotted Owlet

Joining Hands, Deepening Impact

Kokkarebellur residents consider these birds to be blessings that bring them good rains and crops, so they feel it is their duty to protect them. Their lives are filled with exciting stories. It was about 30 years ago that a couple from a bird hunting tribe tried to steal eggs and chicks, but they were caught by the local panchayat. Unable to meet the statutory penalty of INR 100, they were tied to a tree in front of the temple as a punishment.

It is strange that this pelicanry went unnoticed until 1976, with Jerdon's reference as the only exception. Also surprising is the fact that Maharajas of Mysore kept records of wildlife in Mysore area, but there is no mention of Kokkarebellur. Having at last 'discovered' the pelican village in 1976, Karnataka forest department identified Kokkarebellur as being of special interest. In 1994, Hejjarle Balaga (Friends of Pelican), an NGO was formed by Manu from Mysore with a young band of locals. They aimed to inspire and train locals so they would take good care of Kokkarebellur's winged visitors. In addition, they rejuvenated seven wetlands in Kokkarebellur with the aim of increasing bird foraging sites.

One of the rejuvenated wetlands in the outskirts of Kokkarebellur

Hejjarle Balaga's efforts helped Kokkarebellur gain traction. HSBC, WWF-India and the Karnataka forest department are now working together to conserve the biodiversity of this village. Various initiatives have been taken to plant trees and protect nesting sites. In return for not cutting the trees, they offer land owners compensation between INR 500 and 2,500 per tree.

A well-maintained Nature Interpretation Center in Kokkarebellur

Additionally, they built a nice Nature Interpretation Center where you can find a lot of information via an exhibit supplemented by a photo gallery. Seeing my deep interest in reading the exhibits, the gentleman over there was quite intrigued. Later, he provided me with a lot of information that helped me write this travel blog.

Exhibit hall of Nature Interpretation Center

A team member of Hejjarle Balaga explaining the exhibits in detail

Bera Lingegowda, a member of the Hejjarle Balaga, donated 2,500 square feet of his private land for the construction of a pen for nurturing orphaned chicks and sick birds in 1994. There is a fence around them to protect them from dogs and other predators. It is located next to the nature center.

An infant spot-billed pelican is being nurtured in the bird pen

Shimsha River: a story of Kokkarebellur's relocation

The Shimsha river flows about two kilometers from the current village. It's a fast-flowing shallow tributary of the Cauvery. At the bank of this river was the original village. The old village was abandoned after the plague of 1916, and people moved to the current location. It was surprising that the birds also followed them and relocated to the new site, which at that time had no water bodies except for the river nearby. Kokkarebellur residents and these birds share a special bond.

Walking on the sandbanks of Shimsha river can offer you a soothing experience today, and you might even spot some water birds with their prey.

A stunning landscape of Shimsha River

Kokkarebellur - a cradle for life

Nestled in the sugarland of Karnataka, 3.12 sq km area of Kokkarebellu was deemed a community reserve in 2007 under the Wildlife Protection Act. It is the only community protected sanctuary in all of Karnataka to date. It is also home to one of the few remaining breeding sites of spot-billed pelicans in India, a bird which has been classified as Near Threatened by the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature).

It is gaining popularity among bird-watchers and researchers as a knowledge hub for these majestic creatures. It has become a symbol of the incredible symbiotic relationship between humans and birds, as well as the power of collaboration in conservation efforts. Kokkarebellur is truly a haven and hidden gem of Karnataka for these magnificent birds and serves as a reminder of our duty to protect and preserve our natural resources for generations to come.

Interesting facts about Kokkarebellur

- Kokkarebellur is the only community reserve in Karnataka and one of the 45 across the country.

- The area is home to 135 species of birds.

- Around 3,000 painted storks and 500 spot-billed pelicans migrate each year to Kokkarebellur.

- The adult painted stork has a yellow bill, an orange head, and pinkish legs with black and white upper ring coverts. They are 93-102 cm tall with a wingspan of 150-160 cm and 2-3.5 kg of weight.

- Adult spot-billed pelicans have gray feathers on their crests, a gray hindneck, and a brownish tail. Several curly feathers adorn the nape of the hind neck, giving off a greyish color. The pouch is purplish with large pale spots. They are 125-152 cm tall with a wingspan of 213-250 cm and 4-6 kg of weight.

Frequently Asked Questions:

How do I reach Kokkarebellur?

Explore the routes to reach Kokkarebellur, Karnataka - by car, train, bus, or air.

By car: Kokkarebellur is 90 km from Bangalore and 70 km from Mysore. Deviate from Maddur towards Halaguru. It is 12 km from Maddur.

By train: Maddur has a train station that's well connected to Bangalore. Maddur is served by 4-5 trains daily between Bangalore and Mysore.

By bus: KSRTC buses run between Bangalore and Maddur and you can board them at Majestic bus stand. From Maddur, take another bus towards Halaguru and get off at Kokkarebellur.

By air: Bangalore is the most suitable airport since it is well connected to almost all of the cities in India. Mysore also has a small airport with limited flight options.

What are some tips for taking good bird photographs in Kokkarebellur?

I recommend carrying a 70-300 mm or equivalent lens in order to capture bird photographs in Kokkarebellur. Most of the time, you will be shooting from a distance of 30 to 100 feet. The birds are big and since they are not far away, a larger telephoto lens of 500 or 600 mm may provide you with more coverage than you need. The majority of my photographs were taken between 70 and 150 mm in focal length.

What are the bird species found in Kokkarebellur?

The main bird species in Kokkarebellur are Painted Storks, Spot-billed Pelicans, Ibis, and Egrets. Additionally, 135 different species of birds can be observed in and around the village besides these large birds.

Are there any accommodations available in Kokkarebellur?

Kokkarebellur is a tiny village spread across two square kilometers that is not on the tourist radar. Kokkarebellur does not have a hotel or homestay.

Is it safe to visit Kokkarebellur?

Kokkrebellur is absolutely safe to visit. Be mindful of ecological balance and the residents' efforts. However, do not interfere with birds' nesting and lives.

Are there any restrictions on visiting Kokkarebellur?

Kokkrebellur is not a gated sanctuary or restricted area per se. It is a village where birds live alongside residents. As such, there are no specific timing or restrictions.

How can I find a local guide for bird photography in Kokkarebellur?

You can visit the Nature Interpretation Center in Kokkarebellur. There may be a member of Hejjarle Balaga who will accompany you on a village tour.

Disclaimer: This blog may contain affiliate links. At no extra cost to you, we may get a small commission if you buy anything. All products and services we endorse have been personally used or come highly recommended to us. These incomes allow us to keep the community supported and ad-free.

Things To Consider

About the author

Rate the Story

Related Stories

Please share your comment

The first story on bird watching i have ever seen in my life. Very very beautiful indeed.

Name

Email

Comment